Mental Health in Eastern Ontario

- Purpose

- Positive Mental Health

- Public Health Agency of Canada’s Positive Mental Health Framework

- Data Sources

- Local Data

- Self-Rated Mental Health

- Life Satisfaction

- Social Well-Being and Mental Health

- Self-Injury and Suicide

- Life Stress

- Healthy Childhood Development and Mental Health

- Health Status and Mental Health

- Physical Activity and Mental Health

- Substance Use Problems and Mental Health

- Violence and Mental Health

- Sleep

- Family and Societal Indicators and Mental Health

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- References

Click here to consult the Mental Health in Eastern Ontario Executive Summary.

Purpose

Based on the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Positive Mental Health Surveillance Framework indicators and inspired by Ottawa Public Health’s Status of Mental Health in Ottawa report, this snapshot aims to identify the current state of mental health in the Eastern Ontario Health Unit’s region and acts as a baseline for future mental health promotion and surveillance efforts by the Eastern Ontario Health Unit and local community partners.1,6

*Bolded words are defined in the Glossary on page 14.

Positive Mental Health

Influenced by individual, family, community and societal factors, mental health is defined as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” and is an essential component of overall health.2,4 In fact, “there is no health without mental health.”3

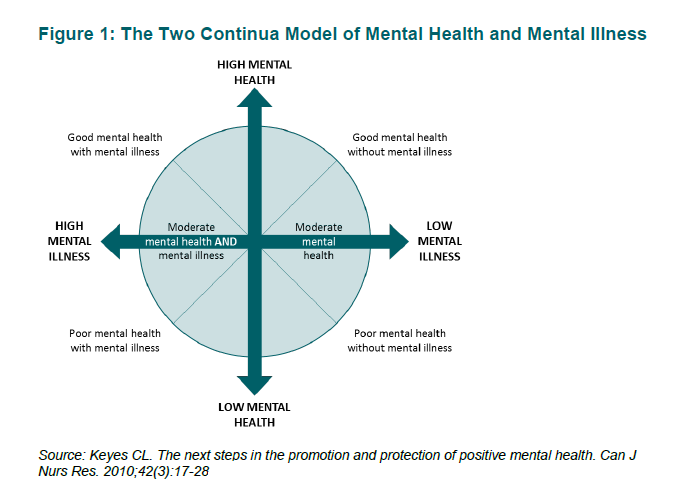

Although related, it is important to distinguish mental health from mental illness. Mental health refers to the range of emotions, thoughts and feelings that everyone experiences, whereas mental illness is a diagnosed disorder that affects the way a person thinks, feels and/or behaves.5 These concepts co-exist (i.e. poor mental health may sometimes lead to mental illness) but are separate.6 For example, it is possible to have poor mental health without the presence of a mental illness, just as it is possible to live with a mental illness but have positive mental health.6 The relationship between mental health and mental illness is best illustrated by Keyes (2010) and his Two Continua Model, as seen in the Ontario Public Health Standards 2018 and shown below.2,34

Figure 1. The Two Continua Model of Mental Health and Mental Illness. Taken from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. (2018). Ontario Public Health Standards 2018.

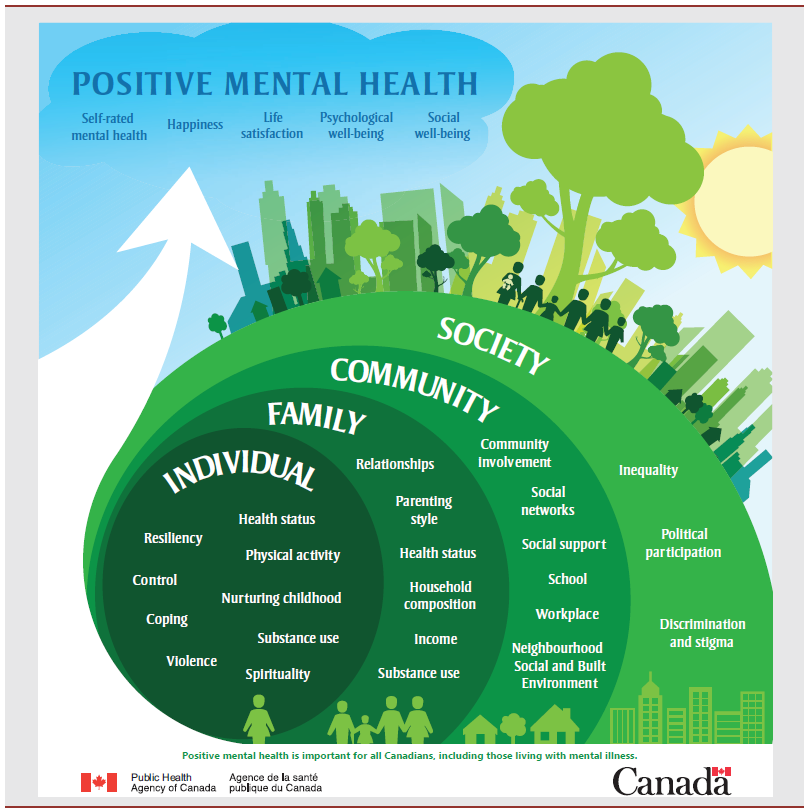

Public Health Agency of Canada’s Positive Mental Health Framework

Released in 2016, this framework was developed to provide “a structure for positive mental health surveillance data that will inform mental health promotion programs and policies across the lifecourse.”7 Considering that a multitude of factors can have an impact on an individual’s mental health, the framework includes 5 outcomes and 25 different indicators.7 These indicators are distributed across 4 ecological levels.7 Figure 1 below summarizes the framework and all of its components.

For more information and to consult the complete framework, see Positive Mental Health Surveillance Framework and Monitoring positive mental health and its determinants in Canada: the development of the Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework.

Figure 2. Positive mental health conceptual framework for surveillance. Taken from Orpana, H., Vachon, J., Dykxhoorn, J., McRae, L., & Jayaraman, G. (2016). Monitoring positive mental health and its determinants in Canada: the development of the Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework. Health promotion and chronic disease prevention in Canada: research, policy and practice, 36(1), 1

Data Sources

Based on availability of local data and potential for future surveillance, the sources listed below were used for this snapshot. When local data was not available for a specific indicator (based on the framework), the indicator was excluded.

Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS):

“The CCHS is a cross-sectional survey that collects information related to health status, health care utilization and health determinants for the Canadian population.”8 It covers the population 12 years of age and over living in the ten provinces and the three territories excluding persons living on reserves and other Aboriginal settlements in the provinces; full-time members of the Canadian Forces; the institutionalized population, children aged 12-17 that are living in foster care, and persons living in the Quebec health regions of Région du Nunavik and Région des Terres-Cries-de-la-Baie-James.8

National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS):

Administered by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, the NACRS contains data for all hospital-based and community-based ambulatory care such as day surgery, outpatient and community-based clinics and emergency departments.9 For this snapshot, the data was accessed through Public Health Ontario and IntelliHEALTH.

Early Development Instrument Cycle (EDI):

“The Early Development Instrument (EDI) measures children’s ability to meet age-appropriate developmental expectations at school entry. It focuses on the overall outcomes for children as a health-relevant, measurable concept that has long-term consequences for individuals and populations. The data from its collection helps monitor the developmental health of our young learners”.10

Census Program:

“The Census Program provides a statistical portrait of the country every five years.”11 Data used for this snapshot was the most recent data from 2016.

Local Data

The following table represents local data for the EOHU region:

| Indicator | Measure | Data | Source |

| Positive Mental Health Determinants | |||

| Self-Rated Mental Health | Proportion of the population aged 12 and over who reported perceiving their own mental health status as being excellent or very good | 70.8% | CCHS 2015/2016 |

| Life Satisfaction | Proportion of the population aged 12 and over who reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their life in general | 91.2% | CCHS 2015/2016 |

| Social Well-Being | Proportion of the population aged 12 and over who reported their sense of belonging to their local community as being very strong or somewhat strong | 71.6% | CCHS 2015/2016 |

| Self Injury | Number (and age-standardized rate per 100 000 population) of ED visits for intentional self-harm (all ages) | 342 (206.1) | NACRS 2017 |

| Suicide | Number (and age-standardized rate per 100 000 population) of mortality from injuries due to intentional self-harm (all ages) | 22 (10.6) | NACRS 2015 |

| Life Stress | Proportion of the population aged 12 and over who reported perceiving that most days in their life were quite a bit or extremely stressful | 18.9% | CCHS 2015/2016 |

| Individual Determinants | |||

| Healthy Childhood Development** | Number (and proportion) of kindergarten children vulnerable in one or more Early Development Instrument domains | 689 (32.8%) | Ottawa Parent Resource Centre (Early Development Instrument Cycle 4 -2014 to 2015) |

| Health Status | Proportion of the population aged 12 and over who reported perceiving their own health status as being either excellent or very good | 60.8% | CCHS 2015/2016 |

| Physical Activity | Proportion of the population aged 18 and over who indicate being physically active (participate in at least 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic physical activity per week, in bouts of 10 minutes or more) | 55.9% | CCHS 2015/2016 |

| Alcohol Use | Proportion of the population 19 and older self-reporting exceeding the low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines (Injury and Chronic Disease) | 48.2% | CCHS 2015/2016 |

| Proportion of the population 12 years and older self-reporting heavy drinking on one occasion, at least once a month in the past year (Heavy drinking = 5 or more drinks for men and 4 or more for women) | 17.7% | CCHS 2015/2016 | |

| Drug Use | Number (and age-standardized rate per 100 000 population) of opioid-related ED visits (all ages) | 65 (31.3) | NACRS 2017 |

| Violence | Number (and age-standardized rate per 100 000 population) of ED visits for injuries due to assault (all ages) | 451 (248.7) | NACRS 2015 |

| Tobacco | Proportion of the population aged 12 and over who reported being a current smoker. Does not consider the number of cigarettes smoked. | 16.4% | CCHS 2015/2016 |

| Sleep** | Proportion of the population reporting an average nightly sleep duration of 7-8 hours per night (all ages) | 49.53% | CCHS 2015/2016 |

| Proportion of the population reporting experiencing trouble going to sleep or staying asleep most or all of the time (all ages) | 19.78% | CCHS 2015/2016 | |

| Proportion of the population reporting never or rarely experiencing refreshing sleep (all ages) | 16.51% | CCHS 2015/2016 | |

| Family Determinants | |||

| Household Composition | Proportion of lone-parent families | 14.8% | Census 2016 |

| Proportion of population who live alone (one-person household) | 26% | Census 2016 | |

| Proportion of population married or living common-law | 61.8% | Census 2016 | |

| Household Income | Prevalence of low-income based on low-income cut-off after tax | 5.3% | Census 2016 |

| Societal Determinants | |||

| Unemployment | Percentage of population aged 15 years and over who is unemployed | 6.6% | Census 2016 |

| Food Security | Percentage of households considered food insecure (marginal, moderate and severe) | 13.4% | CCHS 2012-2014 combined |

CCHS = Canadian Community Health Survey, NACRS = National Ambulatory Care Reporting System, EDI = Early Development Instrument. **= Indicator not in PHAC Framework

Self-Rated Mental Health

A high level of self-rated mental health considers two essential components of positive mental health: feeling good and functioning well.7 This measure provides a broad indication of self-rated mental health in the EOHU region which includes, but is not exclusive to, the presence of mental illness. According to statistics from the CCHS 2015/2016, 70.8% of individuals aged 12 and over reported perceiving their own mental health status as being excellent or very good. This percentage is not significantly different than that of the province (Table 1 below).8,17

Table 1: Population aged 12 and over who reported perceiving their own mental health status as being excellent or very good (CCHS 2015/2016)

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 71.1% | 70.8% |

Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016

Life Satisfaction

Associated with Self-Rated Mental Health and linked to higher life enjoyment, life satisfaction is measured as individuals aged 12 and over reporting being currently satisfied or very satisfied with life in general.8,12 Life satisfaction is important to consider when measuring positive mental health as the ability to enjoy life is associated with factors such as happiness, social well-being and feelings of connectedness.12 All of these not only impact mental health, but overall health as well.12 As with Self-Rated Mental Health, the EOHU’s region has a rate of life satisfaction similar to that of the province.

Table 2: Population aged 12 and over who reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their life in general (CCHS 2015/2016)

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 92.6% | 91.2% |

Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016

Social Well-Being and Mental Health

Associated with the reduction of negative effects of stress or trauma, increased life satisfaction and a reduction in cognitive decline later in life, social well-being is another integral indicator of positive mental health.12 The importance of social well-being on health cannot be overstated and is best demonstrated by looking at the World Health Organization’s definition of health as being “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”13 Furthermore, social inclusion has been identified by VicHealth as being one of the three key determinants indisputably linked to mental health and well-being.14 As a measure of social well-being, the percentage of individuals 12 and over reporting a strong or somewhat strong sense of belonging to their local community was used for this snapshot.8 Once again, the EOHU region is not significantly different than the province in terms of self-reported community belonging.17

Table 3: Population aged 12 and over who reported their sense of belonging to their local community as being very strong or somewhat strong (CCHS 2015/2016)

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 70.9% | 71.6% |

Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016

Self-Injury and Suicide

Suicide is a complex issue which does not have one single cause. Rather, it involves a combination of biological, psychosocial, social, cultural, spiritual, economic and environmental factors.15 Suicide rates were used to help identify the status of mental health in the EOHU region, as many of the factors influencing suicide can also influence mental illness and poor mental health.18 On the one hand, the presence of mental illness (i.e. depression) may increase an individual’s risk of suicide.18 On the other hand, positive mental health and well-being can act as a protective factor helping to guard against suicide.16

Contrary to the other indicators used in this snapshot, there is a statistically significant difference between the rates of self-injury per 100 000 individuals in the EOHU region compared to the rates for all of Ontario. Furthermore, there also seems to be a gender difference, with the rates for self-injury being significantly higher in females in the region. Interestingly and in-line with the literature, the opposite is true for rates of suicide, where rates are higher for males.19

Table 4: Age-standardized rate per 100 000 population of ED visits for intentional self-harm in 2017

| All Population | Males | Females | |||

| Ontario | EOHU | Ontario | EOHU | Ontario | EOHU |

| 154.9 | 206.1* | 105.8 | 101.3 | 205.9 | 316* |

ED = Emergency Department. Data taken from NACRS 2017. *= statistically significant from provincial value

Table 5: Age-standardized rate per 100 000 population of mortality from injuries due to intentional self-harm in 2015

| All Population | Males | Females | |||

| Ontario | EOHU | Ontario | EOHU | Ontario | EOHU |

| 10.8 | 10.6 | 16 | 17.4 | 6.1 | 4.2 |

Data taken from NACRS 2015

Life Stress

Referring back to the definition of mental health by the World Health Organization, an individual with a high level of positive mental health is someone who is equipped and able to deal with the normal stresses of everyday life.4 Effectively dealing with stressful events or situations in daily life requires, among other things, resilience, self-efficacy and coping skills. This is where the importance of life stress as an indicator when measuring mental health status comes from.2,12 In this snapshot, life stress was measured by identifying the percentage of individuals 12 and over who reported perceiving most days as being quite or extremely stressful.17 Although not statistically significant, this percentage seems to be slightly lower in the Eastern Ontario region than in the province.17

Table 6: Population aged 12 and over who reported perceiving that most days in their life were quite a bit or extremely stressful (CCHS 2015/2016)

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 22% | 18.9% |

Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016

Healthy Childhood Development and Mental Health

A person’s early years, the relationships they develop and the situations they experience growing up will have a significant impact on their future health outcomes.2,20 This is an important part of why it is essential to ensure that “every child has the best possible start.”20,2 To measure this, the percentage of children considered vulnerable in one or more domains of the EDI was identified.

The five general domains of the EDI are:

- Physical health and well-being

- Social competence

- Emotional maturity

- Language and cognitive development

- Communication skills and general knowledge.21

In the EOHU region, this percentage was 32.8% for 2014/2015, which is comparable to the provincial average.17

Table 7: Percentage of Kindergarten Children Vulnerable in One or More EDI Domains, 2014 to 2015 (Cycle 4)

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 29.4% | 32.8% |

Data taken from Offord Centre for Child Studies at McMaster University. Statistical significance was not measured.

Health Status and Mental Health

Simply stated, “there is no health without mental health.”3 Health status takes into account holistic health and indicates a person’s self-reported physical, mental and social well-being.17 For this indicator, the proportion of population aged 12 and over who reported perceiving their own health status as either excellent or very good was used.17 In the EOHU region, once again, the value of 60.8% is similar to that of the province.17

Table 8: Population aged 12 and over who reported perceiving their own health status as being either excellent or very good (CCHS 2015/2016)

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 61% | 60.8% |

Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016

Physical Activity and Mental Health

Associated with a healthy lifestyle and contributing to overall health, physical activity has been shown to have a positive effect on mental health outcomes for both adults and children.14 Although no specific dosage of physical activity has been identified as being ideal to improve mental health, every adult should aim to meet the minimum recommendations from the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines (CPAG).22 According to the CPAG, adults 18 to 64 years old should accumulate at least 150 minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity per week, in bouts of at least 10 minutes.22 In the EOHU region, 55.9% of adults self-reported meeting this criteria, which is similar to the provincial average.17

Table 9: Population aged 18 and over who indicate being physically active (CCHS 2015/2016)

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 57.4% | 55.9% |

Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016

Substance Use Problems and Mental Health

Sharing many risk and protective factors, research shows the presence of a link between substance use problems and mental health.23 Including alcohol consumption, tobacco use as well as the use of other drugs, substance use problems can impact overall as well as mental health.22,24 Tables 10 to 13 below compare different substance use/misuse indicators between the EOHU region and the provincial average.

Table 10: Age-standardized percentage of population 19 and over self-reporting exceeding the low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines (Injury and Chronic Disease), 2015/2016

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 44.4% | 48.2% |

Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016

Table 11: Percentage of self-reported heavy drinking on one occasion, at least once a month in the past year (Heavy drinking = 5 or more drinks for men and 4 or more for women), 2015/2016

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 18.2% | 17.7% |

Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016

Table 12: Rate per 100 000 population of opioid-related ED visits in 2017

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 54.6 | 31.3 |

Data taken from NACRS 2017. Statistical significance was not tested.

Table 13: Population aged 12 and over who reported being a current smoker, 2015/2016

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 11.9% | 16.4%* |

*=significantly different from provincial rate. Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016

Violence and Mental Health

As with substance use problems, there is strong evidence linking experiences of violence to mental health problems.25 Specifically, the World Health Organization has stated that alcohol and drug abuse, depression and anxiety, smoking, suicidal thoughts and suicidal behaviours are all potential consequences of violence-related experiences.25 Due to these possible consequences, freedom from discrimination and violence was identified as another of the three key determinants indisputably linked to mental health.14 Although there are many other forms, violence in the region was measured using emergency department assault data from 2017.

Table 14: Rate per 100 000 population of ED visits for injuries due to assault

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 239.1 | 248.7 |

ED = Emergency Department. Data taken from NACRS 2015.

Sleep

Many negative health consequences, including mental health problems, have been associated with inadequate sleep.36 According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society (2015), adults 18 and over should aim to get at least 7 hours of sleep per night to promote optimal health.37 To measure this factor, three separate sleep-related indicators were used for this snapshot: the proportion of the population reporting getting an average of 7 to 8 hours of sleep per night, the proportion of the population experiencing trouble going to sleep or staying asleep most or all of the time, and the proportion of the population reporting never or rarely experiencing refreshing sleep. All three indicators for the EOHU region seem to be comparable to the provincial average, as can be seen in Table 15 below.

Table 15: Sleep

| Percentage of population reporting an average nightly sleep of 7 to 8 hours | Percentage of population reporting experiencing trouble going to sleep or staying asleep most or all of the time | Percentage of population reporting never or rarely experiencing refreshing sleep | |||

| Ontario | EOHU | Ontario | EOHU | Ontario | EOHU |

| 46.04% | 49.53% | 16.21% | 19.78% | 15.5% | 16.51% |

Data taken from CCHS 2015/2016. Statistical significance not measured.

Family and Societal Indicators and Mental Health

Adding to individual factors, the social, economic and physical environments that surround people also have a significant influence on their well-being and mental health and cannot be ignored.2 To measure these social determinants, the following status indicators were used for this snapshot:

• Household composition

• Household income

• Unemployment rate

• Food security

For a list of the social determinants of health, refer to the National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health.32

Table 16: Housing Composition in 2016

| Percentage of lone-parent households | Percentage of population living alone | Percentage of population married or living common-law | |||

| Ontario | EOHU | Ontario | EOHU | Ontario | EOHU |

| 17% | 14.8% | 25.9% | 26% | 57.2% | 61.8% |

Data taken from Census 2016

Table 17: Prevalence of low-income based on low-income cut-off after tax in 2016

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 9.8% | 5.3% |

Data taken from Census 2016

Table 18: Percentage of population aged 15 years and over who are unemployed in 2016

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 7.4% | 6.6% |

Data taken from Census 2016

Table 19: Percentage of households considered food insecure

| Ontario | EOHU |

| 11.9% | 6.6% |

Data taken from CCHS 2014

Conclusion

The purpose of this snapshot was to identify the current state of mental health in the region and act as a baseline for future mental health promotion and surveillance efforts by the EOHU and local community partners. Using the indicators from the Public Health Agency of Canada, this snapshot illustrates the complexities of positive mental health. The data demonstrates that the EOHU region seems to be comparable to the provincial average when it comes to the indicators used in this snapshot, barring a few exceptions (i.e. suicide rates). Nonetheless, there is still a need for local mental health-focused promotion efforts in the region to bring the population to flourish in all aspects of health. Although local data was not available for all indicators, this baseline provides a foundation upon which the EOHU and local community partners can build a broader local mental health surveillance and promotion strategy.

Glossary

Coping: Acting as a protective factor, coping is defined as action-oriented internal efforts made to manage the demands created by stressful events.31

Mental Health: As defined by the Public Health Agency of Canada, mental health is "the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think, act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity".26 Mental health is not simply the absence of mental illness.18

Mental Health Promotion: Founded on the Ottawa Charter of Health Promotion, mental health promotion includes building healthy public policies, creating supportive environments, strengthening community action, developing personal skills and reorienting health services, and is the process of enhancing individual and community capacity to improve mental health.2,28,29

Mental Illness: Taking many forms, mental illness can be described as “alterations in thinking, mood or behaviour—or some combination thereof—associated with significant distress and impaired functioning”.27 Related to mental health, it is important to distinguish both concepts as they are not interchangeable.

Resilience: Identified as a protective factor for mental illness and suicide and a key part of positive mental health, resilience is defined as “the vital sense of flexibility and the capacity to re-establish one’s own balance; the essential feeling of being in control with regard to oneself and to the outside world”.30

Risk and Protective Factors: Factors which can either help individuals deal with events or put them at risk for mental health problems, risk and protective factors will vary during an individual’s lifetime.2,12,33 Mental health promotion should aim to increase protective factors while simultaneously decreasing modifiable risk factors.2

Self-efficacy: This is defined as being a person’s judgement of their own ability to face a certain situation or complete a specific task.35

Substance Use Problems: Substance use problems is a general term encompassing both substance abuse and substance dependence/addiction. Substance Abuse occurs when substance use results in problems in the community, at home and in any other environment.31Substance Dependence/Addiction, on the other hand, is when there is a “pattern of substance use that causes severe distress or impairment”.23

References

- Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention. Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework: Quick Statistics, adults (18 years of age and older), Canada, 2016 Edition. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2016.

- Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (2018). Mental Health Promotion Guideline. Ontario, Canada.

- World Health Organization, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, University of Melbourne. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence and practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/promoting_mh_2005/en

- World Health Organization. Mental Health: A state of well-being 2014 [Available from: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/].

- Government of Canada. The Human Face of Mental Health and Mental Illness in Canada. 2006.

- Ottawa Public Health. Status of Mental Health in Ottawa. June 2018. Ottawa (ON): Ottawa Public Health; 2018.

- Orpana, H., Vachon, J., Dykxhoorn, J., McRae, L., & Jayaraman, G. (2016). Monitoring positive mental health and its determinants in Canada: the development of the Positive Mental Health Surveillance Indicator Framework. Health promotion and chronic disease prevention in Canada: research, policy and practice, 36(1), 1.

- Statistics Canada (2018). Canadian Community Health Survey – Annual Component. Consulted on May 9th 2019. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3226

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (N.D.). National Ambulatory Care Reporting System Metadata (NACRS). Consulted on May 10th 2019. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/national-ambulatory-care-reporting-system-metadata

- Early Development Instrument (2019). EDI in Ontario. Consulted on May 10th 2019. Available from: https://edi.offordcentre.com/partners/canada/edi-in-ontario/

- Statistics Canada (2019). Census Program. Consulted on May 10th 2019. Available from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Improving the Health of Canadians: Exploring Positive Mental Health (Ottawa: CIHI, 2009).

- World Health Organization (n.d.). Constitution. Consulted on May 16th, 2019. Available at https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution

- Keleher, H & Armstrong, R (2005), Evidence-based mental health promotion resource, Report for the Department of Human Services and VicHealth, Melbourne.

- Government of Canada (2016). Working Together to Prevent Suicide in Canada: The Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention. Ottawa, Ontario.

- Government of Canada (2016). Suicide: risks and prevention. Consulted on May 16th 2019. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/suicide-prevention/suicide-risks-prevention.html

- Statistics Canada (2019). Table 13-10-0113-01: Health characteristics, two-year period estimates. Available from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310011301&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.66&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.1&pickMembers%5B2%5D=3.1&pickMembers%5B3%5D=5.4

- Mental Health Commission of Canada (2012). Changing directions, changing lives: The mental health strategy for Canada. Calgary, AB.

- Government of Canada (2016). Suicide in Canada. Consulted on May 16th 2016. Available from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/suicide-prevention/suicide-canada.html

- World Health Organization (2014). Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Social determinants of mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/gulbenkian_paper_social_determinants_of_mental_health/en/

- EDI Early Development Instrument (2019). What is the EDI? Consulted on May 16th 2019. Available from https://edi.offordcentre.com/about/what-is-the-edi/

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (n.d.). Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines: For adults 18-64 years. Consulted on May 17th 2019. Available from https://csepguidelines.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CSEP_PAGuidelines_adults_en.pdf

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addictions (2013). When mental health and substance abuse

problems collide. Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/when-mental-health-and-substance-abuse-problems-collide-topic-summary - Mantoura, P. (2014). Defining a population mental health framework for public health. Montréal, Québec: National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy.

- World Health Organization (2014). Global Status Report on Violence Prevention. Geneva.

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2014). Mental Health Promotion. Consulted on May 21st 2019. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/mental-health/mental-health-promotion.html

- Government of Canada (2006). The human face of mental illness and mental health in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/human-face-mental-health-mental-illness-canada-2006.html

- World Health Organization (1986). Ottawa charter of health promotion. Geneva, World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (2004). Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice: summary report. Geneva, World Health Organization. Available from https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/promoting_mhh.pdf

- Public Health Agency of Canada (2018). Frequently Asked Questions. Consulted on May 21st 2019. Available from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/mental-health/mental-health-promotion/frequently-asked-questions.html

- Taylor, S. E., & Stanton, A. L. (2007). Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol., 3, 377-401.

- National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health (n.d.). Glossary. Consulted on May 21st 2019. Available from http://nccdh.ca/resources/glossary/

- Government of Canada (2015). Protective and risk factors for mental health. Consulted on May 21st 2019. Available from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/protective-risk-factors-mental-health.html

- Keyes CL. The next steps in the promotion and protection of positive mental health. Can J Nurs Res. 2010;42(3):17-28.

- Schunk, D. H. (1991). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26, 207-231.

- Hotte, N. & Lalonde, C. (2019). Sleep Health Assessment. Eastern Ontario Health Unit (Internal document).

- Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, Buysse D, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: a joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38(6):843–844.